"You see all these people?" said the man behind the counter. "They are coming and going as they please. There is no hassle. You must tell people that there is no hassle in Cote d'Ivoire."

He was wearing an Ivoirian military uniform, and was parked comfortably behind a table at the boarder crossing from Ghana. The man was clearly bored and probably underpaid, and he had my passport. Early in the conversation he had made it clear that he didn't intend to give it back until I had paid him CFA3,000 for the privilege of a stamp. When I politely refused, he launched into a lengthy lecture on the state of affairs in Cote d'Ivoire, the treachery of the French and the generosity of the Americans.

"Do you see these computers?" He waved proudly toward two Dell flatscreens in the office behind him. "Who do you think gave them to us? Well, who? The Americans!" All things considered, I was glad that my country had scored highly on the computer front, but the man didn't draw the connection between the American passport in his hand and the machines in the office. He carried on for another 15 minutes, waxing nostalgic about the way things used to be, until I asked for directions to a taxi to Abidjan. He knew quite a lot about that as well. After enumerating all my options in terms of routes and modes of transport, he looked down at the passport and, almost as an afterthought, stamped it and waved me on my way. "Have a good day!" he cried after me. "Tell more tourists to come to Cote d'Ivoire!"

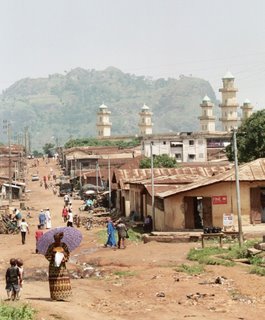

On the road from the border to Abidjan I felt for the first time that I was really back in West Africa. Our minibus hit a barrage (roadblock) every 20 minutes or so, and at each one we had to get out -- usually so they could search the car and hassle the Nigerian girl next to me. Sometimes they simply opened the back and called me out because the captain had spotted a white girl and fancied a chat. I don't know what it all accomplished in terms of security, but I'm sure more than a few bribes were extorted.

Ah, but what a beautiful country! Dense forest, banana and palm groves, gleaming piles of watermelons and bright mangoes stacked by the side of the road. Whenever we stopped the women in my car did a bit of regional shopping, and by the time we got to Abidjan the trunk was filled with pineapples, yams and bunches of live freshwater crabs tied together on a string.

The country may be at war, but it's just so much more fun than Ghana!